In the Ferlo region of Senegal, climate change is making it harder for herders to find water for their cattle. In the Peruvian Amazon, indigenous tribes must remain alert at all times to chase off illegal loggers.

In Los Angeles, city planners are struggling to work out how best to plant 90,000 trees to help cool the hottest neighbourhoods. To solve these problems, all three groups rely on a little-known arm of Google that works closely with environmental advocates around the world.

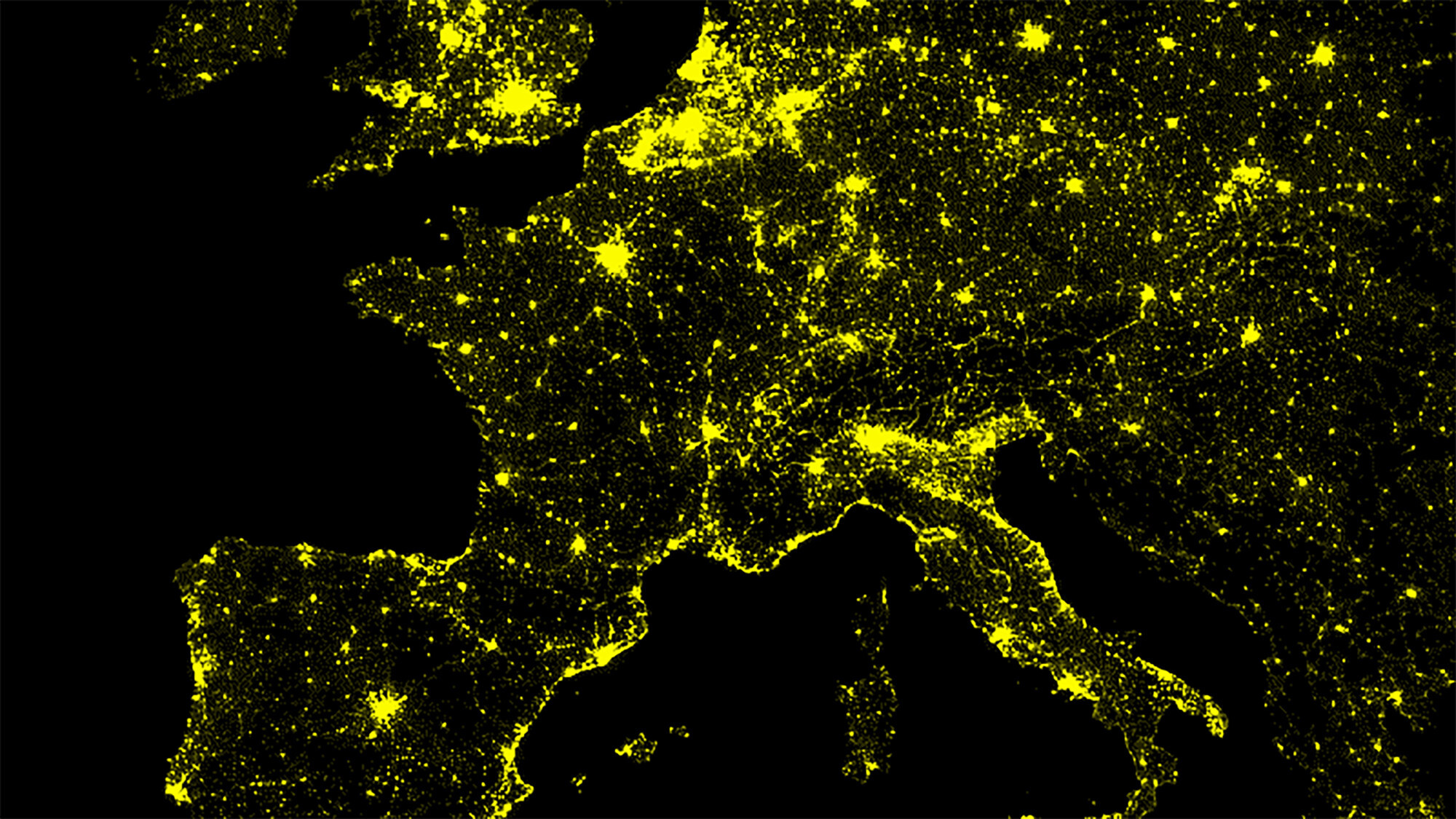

Google Earth Engine has created a vast trove of open-source satellite imagery and augmented it with data-analysis software that makes it relatively easy for skilled outsiders to draw up their own interactive maps.

More important, its team of staff scientists (Google won’t say how many) wrangles massive data sets to answer critical questions for a constellation of pro bono “clients” that includes conservation groups, city agencies, community advocates and researchers.

The 20,000 image files added to the Earth Engine team’s collection each day are more than just static photos. Satellites gather, for example, detailed information on the soil composition more than a foot underground and the amount of water vapour rising from farmland.

Staffers help clients distil relevant information and relay it to the field. Via radio, the nomads in Senegal learn where to find a drink for their cows; bright pink dots on interactive maps inform the indigenous Peruvians of the locations of logging activity; and a shared website targets the spots in LA where trees will likely do the most good.

“The raw data is not enough. Government officials now tell us, ‘We’re drowning in data, but we’re thirsty for insights,’” says Rebecca Moore, who runs the team. “We invented Google Earth Engine to allow scientists to easily analyse data and ask questions about how the climate is changing and answer in seconds or minutes instead of years.”

Other companies, including Amazon.com and Microsoft, have technical services with capabilities comparable to Earth Engine, but experts in the field say the sheer number of work hours Moore’s staff dedicates to volunteer efforts sets it apart.

“It’s just a remarkable level of transparency and information that wasn’t available before,” says Mikaela Weisse, project manager for Global Forest Watch, an open-source online tool that monitors deforestation.

Joe Morrison, a vice-president at satellite imaging company Umbra, who writes a newsletter about the industry, calls Earth Engine the most important contribution to climate science in 50 years.

Of course, Google being Google, Earth Engine’s developers have also been working on commercial applications. In October the company announced a for-profit version of the service, with customers so far including Unilever and Swiss Re. Moore says she sees these efforts as a way to multiply the impact of her team’s conservation work and “build on each other’s best practices”.

The corporate boosterism is a bit out of character for Moore, a software engineer who owes her almost two decades at Google to a penchant for advocacy. The company hired her in 2005, soon after it acquired the underpinnings of Google Earth by buying a satellite mapping company called Keyhole.

Moore had recently made national news for using Keyhole to scuttle a proposed logging project near her property in the Santa Cruz Mountains, south of San Francisco. The local utility was trying to clear 400 hectares of forest and, as Moore’s 3D map showed, might well have damaged a protected watershed and the habitats of endangered species.

Moore grew up in a family of activists on New York’s Long Island. Her father, a civil rights lawyer, won a landmark 1964 case that denied a broadcasting licence to a Mississippi television station airing racial slurs. His work established judicial consideration for the value of federal regulations as a public good.

Moore’s brother, a painter and Aids activist, helped popularise the looped red ribbon that became an international symbol of the disease.

In 2002, after both men died within six months of each other, Moore took stock of her life and decided she wasn’t happy with the kind of coding work she was doing. Her passion for mountaineering – she had led groups up the Himalayas in India and Denali in Alaska – left her with a deep appreciation for a good map.

The anti-logging project, her first effort, established her as an expert on the emerging technology. She sent Keyhole so many notes with suggestions on ways to debug their software that when Google bought the company, the team made Moore’s hire a priority.

At Google, Moore gravitated towards environmental mapping projects. In 2008, the company asked employees to brainstorm philanthropic initiatives that fit its capabilities.

To Moore, there was an obvious opening: for decades, United States and European government satellites had collected a vast store of data about the Earth and its atmosphere, information that was virtually impossible for the public to sift through because it was stored on reels of magnetic tape sitting in a federal mountain vault in South Dakota.

In digital form it would comprise many petabytes of data, each one the equivalent of 500 billion pages of printed text. That didn’t faze Moore. “It sounded like something Google should do,” she says.

By the end of 2009, she and two colleagues had created a demo version of Earth Engine that could track Latin American deforestation in high-resolution detail almost as it happened. Over the years she has briefed environmental activist Al Gore on Earth Engine’s capabilities and advised actor and activist Woody Harrelson on its use as a tool to track mountaintop removal mining.

But it is people like Gilberto Câmara, a Brazilian researcher who’s led the development of satellite monitoring in the Amazon, who have become Moore’s most frequent partners. Over the past decade her team has grown better able to collaborate with and meet the needs of activists and researchers. She has added subject matter experts, including geologists and hydrologists, and uploaded custom data sets from sources other than satellites.

She says the corporate product, still in its early days, is in keeping with her long-time mission. Unilever says it is using Earth Engine to make sure its palm oil, a key ingredient in many consumer goods, doesn’t come from illegal logging in tropical forests.

The company is trying to follow through on its pledge to keep its supply chain free of deforestation. It monitors 17 million hectares of farms and tracks the footprints of agriculture and traffic through 77,000 small villages to assess which of its 1,900 mills might be receiving palm oil from illegal farms.

The intel Earth Engine offers can come with risks. In South Sudan, Cloud to Street, a company that maps drought and flood zones in communities at risk from climate change, was warned not to make its maps public after locals worried that gangs of marauders from rebel factions in the ongoing civil war might use them to target vulnerable villages. “Transparency isn’t always a good thing,” says Beth Tellman, Cloud to Street’s chief science officer.

For many of Earth Engine’s fans, the biggest worry is that Google might take it away or start charging academics and activists beyond their ability to pay. Moore says that won’t happen. But if it does, the pain would be widespread. Câmara says his field can be measured cleanly in terms of Moore’s work. “We break it down,” he says, “to before and after Google Earth Engine.”

Case study: Cloud to Street

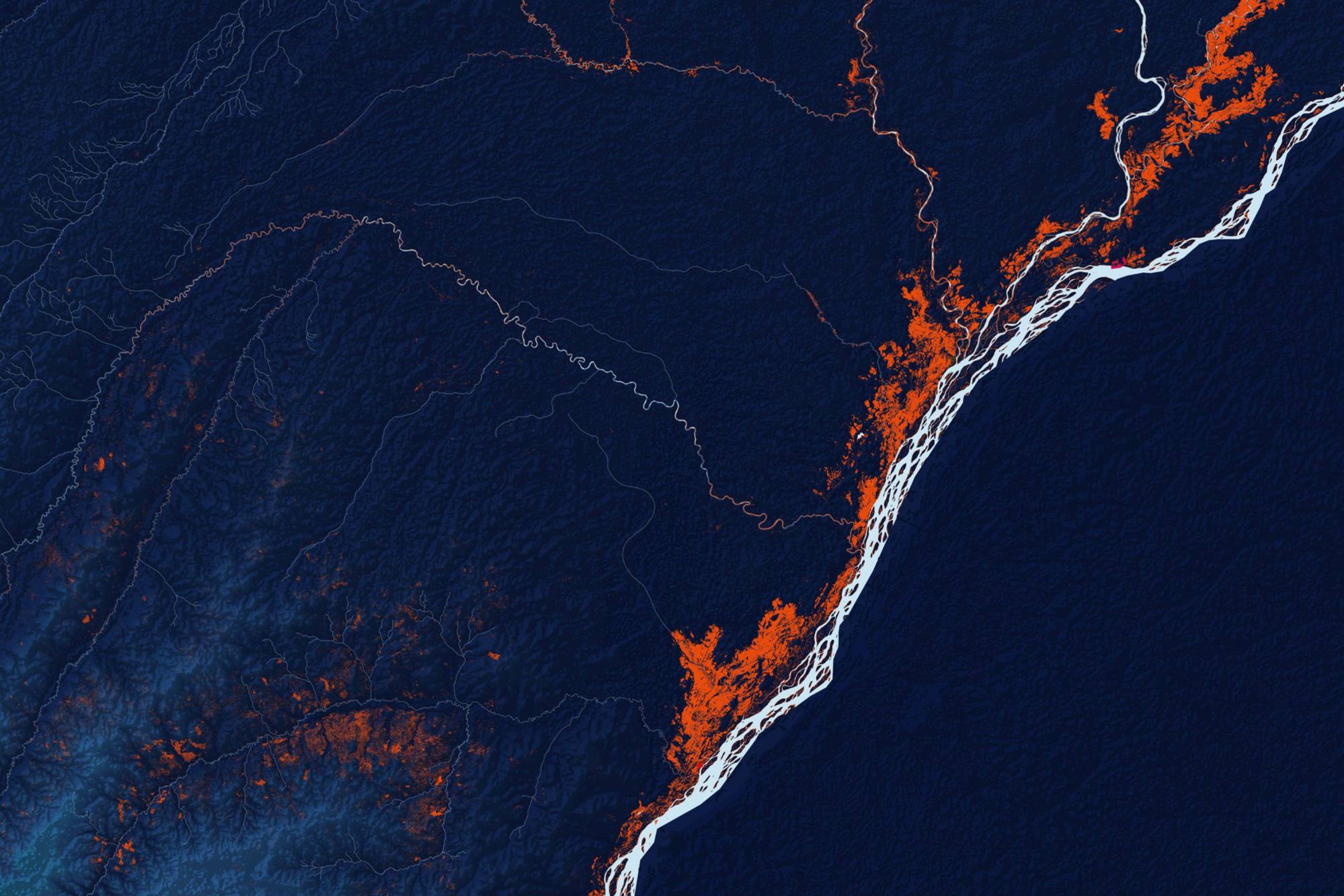

Predicting floods in the Republic of the Congo

For the past few years, Cloud to Street has used Google Earth Engine to help its own website predict the intensity, duration and impact of flooding in the Republic of the Congo. The company began working with Moore’s team after floods in the central African country in 2017 damaged crops, homes and roads, and left aid workers dependent on ground-level observers to report conditions.

Cloud to Street, which works with the United Nations World Food Programme and a smattering of governments and insurers, supplements its analysis with text and photo updates from locals, but the meat of its prediction algorithm runs on Earth Engine data.

Cloud to Street users can see a map of the area that tracks the path of rising water towards population centres, receive text messages about blocked roads and other hazards, and text in questions themselves.

On a macro level, Cloud to Street has helped the Republic of the Congo and other countries gather the data needed to declare that a flood has qualified as a national emergency, a key step before they can ask for international aid.

Traditionally, that process takes months. But after a severe flood in late 2019, the site showed evidence of devastation quickly enough to secure millions in aid in just days.

But it wasn’t only money that the site secured. Months earlier, Jean-Martin Bauer, a senior adviser with the World Food Programme, sent Cloud to Street CEO Bessie Schwarz a WhatsApp message noting that 11,000 refugees had just arrived in a low-lying part of the Republic of the Congo and asking whether they were at risk.

With help from Earth Engine, Schwarz’s site led the UN to relocate 7,000 people to safety. By the time the 2019 flood came and washed away that refugee camp entirely, the rest had found higher ground, too.

Case study: OpenET

Droughts in the US

The American West is parched to a record-breaking degree, yet in most Western states there has been no way for the public to measure whether their neighbours are using more than their share of the limited water supply.

“If you are a water management district or actor of any scale and trying to manage a budget without knowing how much water is being consumed, it is just a critical data gap,” says Robyn Grimm, a water systems scientist and director at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

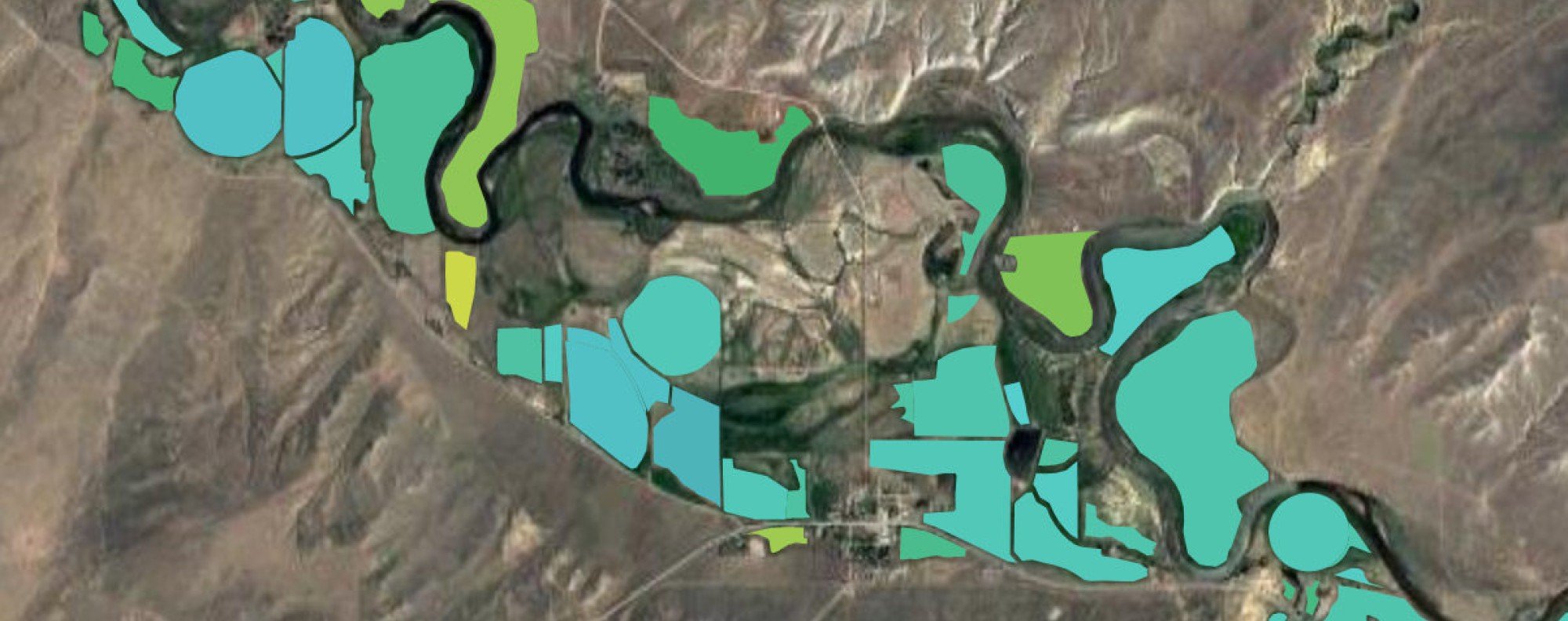

Grimm led the development of OpenET, a new website using Earth Engine support and processing power to show more clearly how much water is being consumed field by field.

EDF and a consortium of science and advocacy partners, including Nasa, announced the site’s creation on October 21, 2021. So far it is being used by farmers and local officials to measure evapotranspiration (ET), the amount of water vapour that rises both from the surface of a patch of soil and from the leaves of the plants growing on it.

ET is a rough gauge of how much water each plot of land consumes, but Nasa satellites can measure it down to about a quarter of an acre. The OpenET system allows users to track it across land and time.

If they zoom out, they can see a patchwork of fields in blues and greens representing relative water use. “Now water managers can take the next step,” Grimm says, though she warns that lay readers shouldn’t jump to conclusions about what the maps mean.

That is not enough to assuage some concerns from farmers, the biggest water users by far, that a bureaucrat might be about to shut down their livelihood.

“It will cause some anxiety and concern in the agriculture community now that everybody can see exactly where and how they’re applying water,” says Mark Owens, a state representative in Oregon who is also a farmer. “But the public should have the right to know how water is being used.”

There are lots of reasons two fields, even those side by side, might consume different amounts of water: different crops, different soil quality, older orchards. And OpenET can’t distinguish between rainwater and water pumped from the ground or taken from the public tap.

Still, Owens, who grows alfalfa and has been testing OpenET for three years, says the platform has helped him use less water than he thought he needed.

Climate change is making it tougher for even the experts to know how much is just enough. With the software’s help, he says, he redesigned his irrigation system and his watering patterns. “For my location and crop type,” he says, “we are now doing a great job.”