Many countries in Africa and those experiencing armed conflict are struggling to access money set aside to prepare them for climate change, according to new research.

The study finds that nearly half of the world’s most climate-vulnerable nations, from Haiti to Afghanistan, missed out on the first round of grants for adaptation projects from the UN’s Green Climate Fund (GCF).

African nations were particularly badly affected, with no money going to projects in 13 of the 30 “least developed” states across the continent.

The largest fund of its kind, GCF was explicitly created to help the parts of the world that are most exposed to climate hazards. It handed out more than $5bn during its first wave between 2015 and 2019, contributing to wealthy nations’ wider climate finance obligations.

The fund says its portfolio of projects has roughly doubled in value since the new study’s cut-off date in 2019 and “huge strides” have been taken to improve access since then.

However, some vulnerable nations are still yet to receive adaptation support and experts tell Carbon Brief that lack of resources, data and infrastructure continue to restrict access.

‘Particularly vulnerable’

The idea that “developed” countries should give climate finance to “developing” nations is enshrined in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Many see it as an issue of climate justice, based on historical responsibility for global warming.

A commitment by wealthy nations to give collectively $100bn in climate finance a year by 2020 was a core element of the Paris Agreement, yet they are not expected to reach this goal until 2023.

The GCF was established under the UNFCCC as a key part of this effort. It is mandated to mobilise funds for cutting emissions and adapting to global warming in developing countries, with a particular focus on those with low incomes and high climate vulnerability.

Adaptation projects, such as planting trees to prevent the expansion of deserts or building flood defences, are particularly important for global-south nations, which tend to be more vulnerable to climate impacts. So far, adaptation has been severely underfunded.

The GCF states that when allocating adaptation funds:

“The board will take into account the urgent and immediate needs of developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.”

It defines “particularly vulnerable” countries as “including least developed countries (LDCs), small island developing states (SIDS) and African states”, and aims for at least 50% of its adaptation funds to go to these nations.

However, while the GCF has provisions in place that are meant to help these countries claim their share of funding, many have been hindered by complex processes and lack of capacity.

“Unfortunately, most climate vulnerable, least-developed and developing countries have found it a bit difficult to access,” Dr Emmanuel Tachie-Obeng of the Ghana Environmental Protection Agency and the Climate Vulnerable Forum, tells Carbon Brief.

This was a key issue raised by the new research, according to the study’s lead author, Prof Matthias Garschagen of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. He tells Carbon Brief:

“What happens to those countries that should be prioritised but are lacking the capacities to actually put in the proposals and…pull these projects through?”

Missing countries

In their study, published in Global Environmental Change, Garschagen and his co-author Deepal Doshi set out to assess whether the initial round of GCF adaptation funding had succeeded in its goal of helping the most vulnerable nations.

The researchers examined the $2.5bn in adaptation finance provided between 2015 and 2019 to 84 of the 154 countries that are eligible for GCF funds. This is roughly half the total, with the remainder going on projects to cut emissions, such as installing renewable power.

Overall, the study found that 54% of adaptation funds in the first GCF allocation period went to small islands, LDCs and African countries. This means that, by its own measure, the body has succeeded in distributing half of its money to vulnerable states.

However, this is a relatively crude way of targeting the money considering the range of wealth and vulnerability in these groups, which include upper middle-income countries, such as South Africa, as well as low-income countries, such as Somalia.

Garschagen and Doshi highlight the lack of more detailed prioritisation as an issue with the GCF’s approach and try to identify the “most vulnerable” countries in their analysis.

The researchers analysed recipient nations’ level of vulnerability to climate change in a more granular fashion, using existing indices, and their institutional capacity using data from the World Bank. They then ranked countries on a spectrum of vulnerability from very high to low.

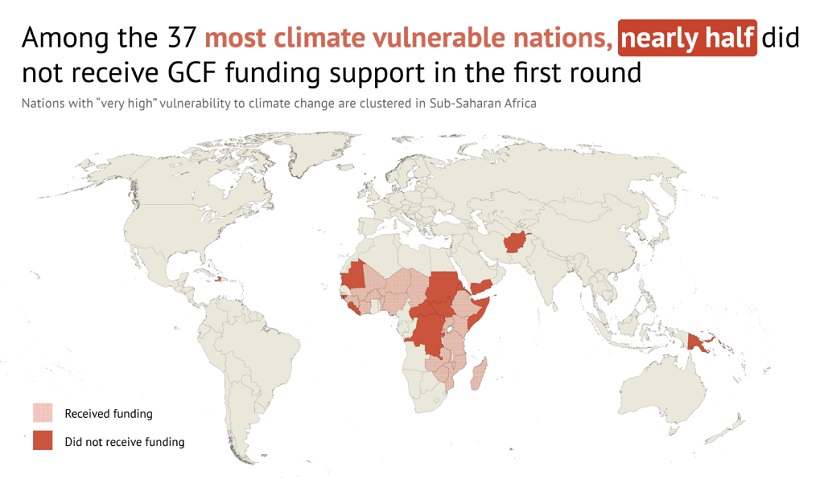

Using this ranking, they found that 16 of the 37 nations categorised as most vulnerable to climate change had not received GCF project funding. The map below highlights the nations identified as most vulnerable in the study, with those missing out on funds coloured in red.

Among them were countries affected by conflict, such as Afghanistan and Yemen, and some of the lowest-income states in the world, such as Burundi and the Central African Republic.

The researchers also found that the share of adaptation funds was “surprisingly small” for certain country groupings. Notably, 13 of the 30 LDCs in Africa did not receive any project funding at all.

Capacity and competition

The paper also considers why some countries are struggling to access support through the GCF. Garschagen and Doshi note that weak “institutional capacity and bureaucratic fitness” have made it harder for many to access funds, especially through their own institutions.

They found that only 6% of successful nations had managed to obtain funds through their national institutions, with most relying on international bodies such as the World Bank to broker the process.

Regional experts tell Carbon Brief that lack of data, expertise and resources have all been barriers to navigating the GCF system and supporting climate projects.

“The process is lengthy and extremely complicated. Many countries give up along the way because it requires significant investment,” says Kulthoum Omari-Motsumi of the Africa Adaptation Initiative.

Samim Hoshmand, who was Afghanistan’s climate change director before he fled the country last year, tells Carbon Brief that accessing the GCF can be “painfully slow” for countries like his:

“The GCF is a competitive fund…There are countries like Tajikistan, Pakistan, India and many others that are stable, that have research, stable organisations and expertise. They can prepare a proposal very well.”

While the fund’s rules exist to avoid misspending, Gaia Larsen, a climate finance expert at the World Resources Institute (WRI), tells Carbon Brief this is a “difficult balance to strike since too many cumbersome rules can mean that money doesn’t reach those in most need”.

The GCF’s “readiness” funds, which made up $172m of additional funding in the period assessed by Garschagen and Doshi, are meant to help countries overcome this by preparing them to navigate the system.

Indeed, the analysis showed that only 5% of eligible countries received funding without first accessing these funds. While most of the “very high vulnerability” nations at least received readiness funds, Eritrea, Somalia and Yemen had received nothing at all.

But the authors say that the GCF and other major climate funds should go beyond this kind of support to ensure that vulnerable people are not left behind.

They point to a simplified approval process that has been piloted for smaller-scale projects as an area that should be expanded. WRI analysis released last year also backed such a proposal, as well as more support for national ownership of funding applications.

Sreeja Jaiswal, an economist at the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, tells Carbon Brief that while the new paper is welcome, it places too much emphasis on nations’ weak institutional capacities:

“Do LDCs’ weak institutional capacities prevent them from accessing finance? Or lack of access to finance results in weak institutional capacity and reinforces their poverty?”

She says this also “sidesteps the elephant in the room” – namely the co-financing requirements the GCF places on recipients, which she adds could be scrapped for vulnerable countries.

‘Huge strides’

Since its “initial resource mobilisation” finished in 2019, the GCF has begun its “first replenishment” and continued handing out grants to countries in need.

A spokesperson tells Carbon Brief that the new study’s cut-off point excludes a considerable portion of funding, given that the total it has distributed has roughly doubled from $5.1bn to $10bn since then. Of this, $3.8bn has gone to adaptation projects.

He also says that “huge strides have been taken to increase access to adaptation finance for developing countries”, with 108 nations now approved for at least one adaptation project, up from 84 in this analysis. Five LDCs in Africa have still not received any adaptation funds.

Garschagen tells Carbon Brief that climate finance is likely to be more competitive in the future as climate impacts become more severe, especially if wealthier countries continue to underdeliver.

With “readiness” funding and other support already being rolled out, a key metric will be whether such measures actually result in more countries directly accessing GCF funds, he adds. Garschagen also says:

“In the next round of mobilisation we really need to have a careful eye on whether that pattern of the first mobilisation persists, because if it does we are now onto a problematic track.”

Garschagen, M. and Doshi, D. (2022) Does funds-based adaptation finance reach the most vulnerable countries?, Global Environmental Change, doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102450

Many countries in Africa and those experiencing armed conflict are struggling to access money set aside to prepare them for climate change, according to new research.

The study finds that nearly half of the world’s most climate-vulnerable nations, from Haiti to Afghanistan, missed out on the first round of grants for adaptation projects from the UN’s Green Climate Fund (GCF).

African nations were particularly badly affected, with no money going to projects in 13 of the 30 “least developed” states across the continent.

The largest fund of its kind, GCF was explicitly created to help the parts of the world that are most exposed to climate hazards. It handed out more than $5bn during its first wave between 2015 and 2019, contributing to wealthy nations’ wider climate finance obligations.

The fund says its portfolio of projects has roughly doubled in value since the new study’s cut-off date in 2019 and “huge strides” have been taken to improve access since then.

However, some vulnerable nations are still yet to receive adaptation support and experts tell Carbon Brief that lack of resources, data and infrastructure continue to restrict access.

‘Particularly vulnerable’

The idea that “developed” countries should give climate finance to “developing” nations is enshrined in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Many see it as an issue of climate justice, based on historical responsibility for global warming.

A commitment by wealthy nations to give collectively $100bn in climate finance a year by 2020 was a core element of the Paris Agreement, yet they are not expected to reach this goal until 2023.

The GCF was established under the UNFCCC as a key part of this effort. It is mandated to mobilise funds for cutting emissions and adapting to global warming in developing countries, with a particular focus on those with low incomes and high climate vulnerability.

Adaptation projects, such as planting trees to prevent the expansion of deserts or building flood defences, are particularly important for global-south nations, which tend to be more vulnerable to climate impacts. So far, adaptation has been severely underfunded.

The GCF states that when allocating adaptation funds:

“The board will take into account the urgent and immediate needs of developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.”

It defines “particularly vulnerable” countries as “including least developed countries (LDCs), small island developing states (SIDS) and African states”, and aims for at least 50% of its adaptation funds to go to these nations.

However, while the GCF has provisions in place that are meant to help these countries claim their share of funding, many have been hindered by complex processes and lack of capacity.

“Unfortunately, most climate vulnerable, least-developed and developing countries have found it a bit difficult to access,” Dr Emmanuel Tachie-Obeng of the Ghana Environmental Protection Agency and the Climate Vulnerable Forum, tells Carbon Brief.

This was a key issue raised by the new research, according to the study’s lead author, Prof Matthias Garschagen of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. He tells Carbon Brief:

“What happens to those countries that should be prioritised but are lacking the capacities to actually put in the proposals and…pull these projects through?”

Missing countries

In their study, published in Global Environmental Change, Garschagen and his co-author Deepal Doshi set out to assess whether the initial round of GCF adaptation funding had succeeded in its goal of helping the most vulnerable nations.

The researchers examined the $2.5bn in adaptation finance provided between 2015 and 2019 to 84 of the 154 countries that are eligible for GCF funds. This is roughly half the total, with the remainder going on projects to cut emissions, such as installing renewable power.

Overall, the study found that 54% of adaptation funds in the first GCF allocation period went to small islands, LDCs and African countries. This means that, by its own measure, the body has succeeded in distributing half of its money to vulnerable states.

However, this is a relatively crude way of targeting the money considering the range of wealth and vulnerability in these groups, which include upper middle-income countries, such as South Africa, as well as low-income countries, such as Somalia.

Garschagen and Doshi highlight the lack of more detailed prioritisation as an issue with the GCF’s approach and try to identify the “most vulnerable” countries in their analysis.

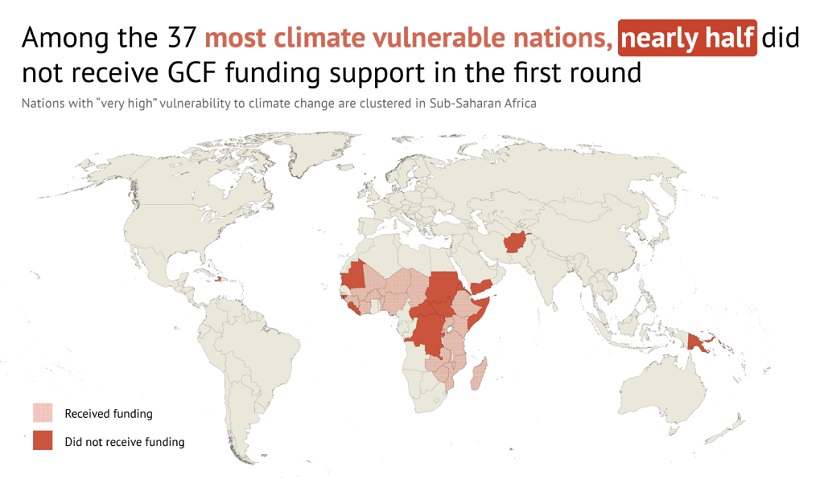

The researchers analysed recipient nations’ level of vulnerability to climate change in a more granular fashion, using existing indices, and their institutional capacity using data from the World Bank. They then ranked countries on a spectrum of vulnerability from very high to low.

Using this ranking, they found that 16 of the 37 nations categorised as most vulnerable to climate change had not received GCF project funding. The map below highlights the nations identified as most vulnerable in the study, with those missing out on funds coloured in red.

Among them were countries affected by conflict, such as Afghanistan and Yemen, and some of the lowest-income states in the world, such as Burundi and the Central African Republic.

The researchers also found that the share of adaptation funds was “surprisingly small” for certain country groupings. Notably, 13 of the 30 LDCs in Africa did not receive any project funding at all.

Capacity and competition

The paper also considers why some countries are struggling to access support through the GCF. Garschagen and Doshi note that weak “institutional capacity and bureaucratic fitness” have made it harder for many to access funds, especially through their own institutions.

They found that only 6% of successful nations had managed to obtain funds through their national institutions, with most relying on international bodies such as the World Bank to broker the process.

Regional experts tell Carbon Brief that lack of data, expertise and resources have all been barriers to navigating the GCF system and supporting climate projects.

“The process is lengthy and extremely complicated. Many countries give up along the way because it requires significant investment,” says Kulthoum Omari-Motsumi of the Africa Adaptation Initiative.

Samim Hoshmand, who was Afghanistan’s climate change director before he fled the country last year, tells Carbon Brief that accessing the GCF can be “painfully slow” for countries like his:

“The GCF is a competitive fund…There are countries like Tajikistan, Pakistan, India and many others that are stable, that have research, stable organisations and expertise. They can prepare a proposal very well.”

While the fund’s rules exist to avoid misspending, Gaia Larsen, a climate finance expert at the World Resources Institute (WRI), tells Carbon Brief this is a “difficult balance to strike since too many cumbersome rules can mean that money doesn’t reach those in most need”.

The GCF’s “readiness” funds, which made up $172m of additional funding in the period assessed by Garschagen and Doshi, are meant to help countries overcome this by preparing them to navigate the system.

Indeed, the analysis showed that only 5% of eligible countries received funding without first accessing these funds. While most of the “very high vulnerability” nations at least received readiness funds, Eritrea, Somalia and Yemen had received nothing at all.

But the authors say that the GCF and other major climate funds should go beyond this kind of support to ensure that vulnerable people are not left behind.

They point to a simplified approval process that has been piloted for smaller-scale projects as an area that should be expanded. WRI analysis released last year also backed such a proposal, as well as more support for national ownership of funding applications.

Sreeja Jaiswal, an economist at the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, tells Carbon Brief that while the new paper is welcome, it places too much emphasis on nations’ weak institutional capacities:

“Do LDCs’ weak institutional capacities prevent them from accessing finance? Or lack of access to finance results in weak institutional capacity and reinforces their poverty?”

She says this also “sidesteps the elephant in the room” – namely the co-financing requirements the GCF places on recipients, which she adds could be scrapped for vulnerable countries.

‘Huge strides’

Since its “initial resource mobilisation” finished in 2019, the GCF has begun its “first replenishment” and continued handing out grants to countries in need.

A spokesperson tells Carbon Brief that the new study’s cut-off point excludes a considerable portion of funding, given that the total it has distributed has roughly doubled from $5.1bn to $10bn since then. Of this, $3.8bn has gone to adaptation projects.

He also says that “huge strides have been taken to increase access to adaptation finance for developing countries”, with 108 nations now approved for at least one adaptation project, up from 84 in this analysis. Five LDCs in Africa have still not received any adaptation funds.

Garschagen tells Carbon Brief that climate finance is likely to be more competitive in the future as climate impacts become more severe, especially if wealthier countries continue to underdeliver.

With “readiness” funding and other support already being rolled out, a key metric will be whether such measures actually result in more countries directly accessing GCF funds, he adds. Garschagen also says:

“In the next round of mobilisation we really need to have a careful eye on whether that pattern of the first mobilisation persists, because if it does we are now onto a problematic track.”

Garschagen, M. and Doshi, D. (2022) Does funds-based adaptation finance reach the most vulnerable countries?, Global Environmental Change, doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102450