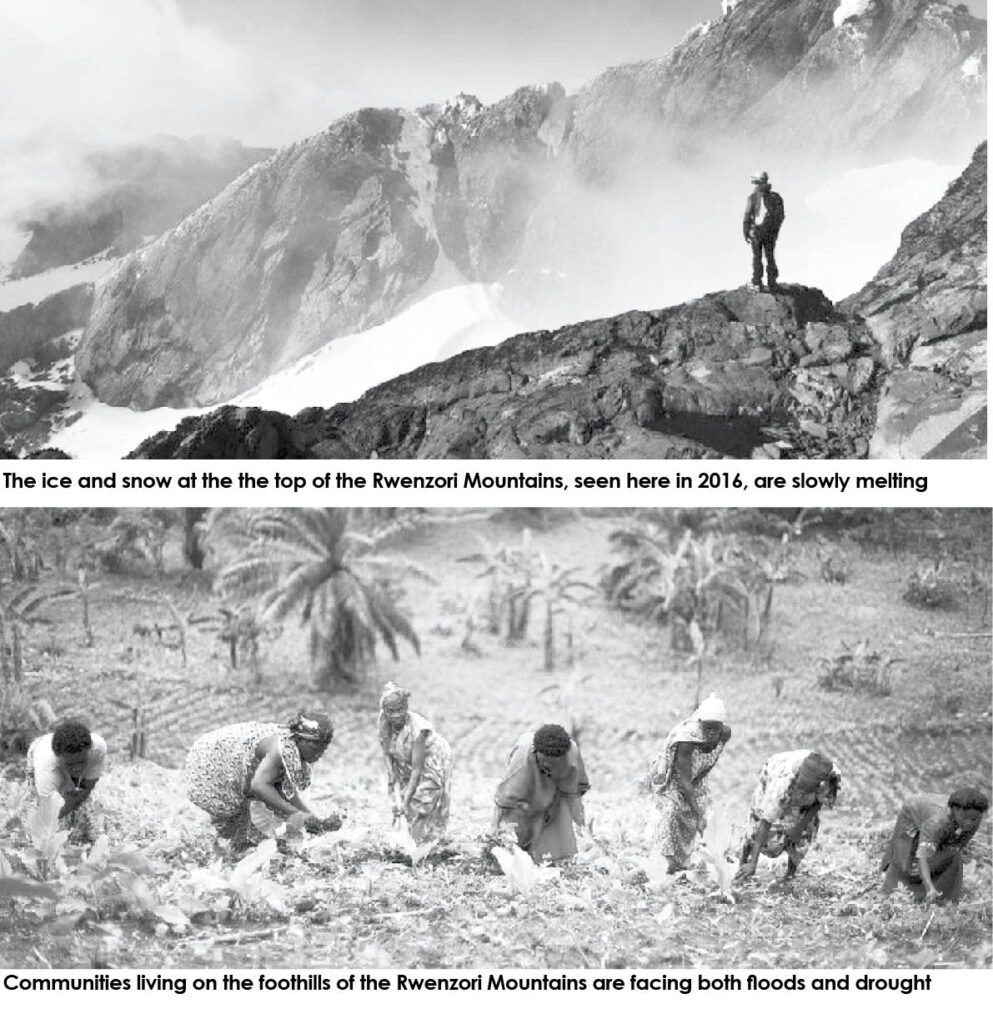

Ronah Masika remembers when she could still see the snowy caps of the Rwenzori mountains, a Unesco World Heritage site on the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The view was stunning every time she travelled from her home in Kasese town to the Ugandan capital, Kampala – and it was not even that long ago.

But now she cannot even catch a glimpse of the ice because the glacier is receding. And it is not only the view that has changed.

Ms Masika recalls her grandmother used to grow beans to feed her family, and they would last until a new crop was ready to be harvested.

“Now I and other people find it difficult to sustain ourselves with what we plant at home, because everything gets destroyed by floods or drought. It’s either too much drought or too much rain.

“It’s making me uncomfortable, thinking of how the next generation is going to survive this horrible situation,” says Ms Masika, who now works on a project to mitigate the impact of the shifting environment.

Climate change is affecting the Rwenzori Mountains in different ways.

The most visible is the rapid loss of the ice field, which shrunk from 6.5 sq km in 1906 to less than one sq km in 2003, and could completely disappear before the end of this decade, research shows.

In 2012, forest fires reached altitudes above 4,000m, which would have been inconceivable in the past, devastating vegetation that controlled the flow of the rivers downstream.

Since then, the communities living at the foot of the Rwenzori have suffered some of the most destructive floods the area has ever seen, coupled with a pattern of less frequent but heavier rainfall.

In May last year, five local rivers burst their banks after heavy rains. The waters came down the mountain carrying large boulders, sweeping away houses and schools and razing the entire town of Kalembe to the ground.

Around 25,000 houses were destroyed and 173,000 people were affected.

While science may provide an explanation for these events, the local Bakonzo culture has another way of framing them – according to their beliefs, they happen because the gods are angry.

“The Bakonzo have a very strong attachment to the snow and the water,” says Simon Musasizi, a programme manager at the Cross-Cultural Foundation of Uganda (CCFU).

“They believe that their god, Kithasamba, lives in the snow, and that the snow is actually the frozen sperm of their god.”

The name Rwenzori comes from rwe nzururu, which means “place of snow” in the Bakonzo language. There are 30 gods associated with different natural resources living on the mountain, according to Bakonzo cosmology.

But deforestation and rapid population growth around the sacred mountain, as well as the melting glacier, are changing things.

During last year’s floods, the water submerged hot springs and washed away the vegetation around a waterfall that was used as a place for rituals. Since then, spiritual leaders have been unable to perform those ceremonies.

Other spiritual sites are getting eroded or filled up with silt and the destruction of the vegetation has weakened the banks in many areas. All this is threatening centuries-old rituals.

“Most likely, many of these customs will gradually became rare or they won’t happen any more, because everything is shifting,” Mr Musasizi says.

The Bakonzo community is made up of around one million people living on both sides of the border between Uganda and DR Congo, and their heritage could be lost as a result of climate change.

“The consequences of climate change are particularly acute at the tropics,” says Richard Taylor, a geographer at University College London, who has led research on the Rwenzori Mountains.

“One or two degrees of warming at the Equator has a much bigger impact on climate and water budgets than one or two degrees of warming in London, Paris or New York.”

The intensification of weather patterns observed in the mountains is happening throughout the tropics.

Prof Taylor, who co-led expeditions from 2003 to 2007 to measure the changes in the Rwenzori glaciers, says the loss of ice fields in the tropics is a tell-tale signal of global warming.

Restoring and protecting areas affected by climate change is key to preserving cultural heritage too.

As part of a project to do this, Mr Musasizi says there is an agreement with the community about which trees are going to be planted to best reinforce the riverbanks, including bamboos and native trees.

Ms Masika, whose job it is to liaise with the local people, says the community already had answers for some of the problems.

“For example, they know what type of vegetation should be planted at what level on the mountain. They know which ones are strong enough to be planted along the river to stop the floods.

“They know they are supposed to plant along the riverbank because it is food to the water god. And when the water god is fine, he doesn’t cause floods.

“Climate change is understood in the culture, and they have some suggestions that can help us mitigate this situation.”

The lessons are being shared with other institutions working to protect cultural heritage from climate change, mainly in East and North Africa and the Middle East.

Finding solutions that highlight the close link between the Bakonzo culture and the natural environment has been a surprise for Ms Masika, who grew up in a Christian household where little was said about it.

Now one of her favourite spots is the Embugha or Rwagimba hot springs, that the Bakonzo believe have physical and spiritual healing powers, particularly for skin diseases.

“When we started this project, my skin was itching all over. But every time I visited the springs, I made sure I bathed in the water,” she said.

“It’s so hot when you sit there, you feel like you’re burning. Then you go to the river, which is just next to the hot pool, and the water is so cold you feel like you’re freezing.

“By the time you leave, your body is feeling light, and since then I no longer feel itchy.”

Culled from the BBC.