Zakari Usman with agency reports

Deep in Liberia’s forested hinterland, thousands of refugees who fled conflict in Ivory Coast have been waiting in limbo, impatient to rebuild their shattered lives back home but unable to leave.

They were preparing their return last summer when suddenly they found themselves trapped in a major tropical disease outbreak as Ebola ravaged their host nation, prompting the government to close its borders.

“I was about to leave when the process was stalled by the Ebola virus,” Saint Lamco Deniohon revealed outside his makeshift home at the PTP refugee camp, in the south-eastern county of Grand Gedeh.

Over 220,000 Ivorians found refuge in Liberian camps after fleeing the 2002 civil war and a 2011 conflict that claimed 3,000 lives as former president Laurent Gbagbo refused to accept election defeat to Alassane Ouattara.

Most made their way home but around 38,000 have remained, housed in three camps and various communities along Liberia’s border with Ivory Coast.

Deniohon ended up in PTP, the west African country’s largest camp, after fleeing with his wife and two children in 2011.

He feared the family might never see home again as the rising Ebola death toll spread panic throughout west Africa, claiming almost 11,000 lives since December 2013, all but about 15 in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone.

But Liberia began to get on top of the epidemic in November last year, and the country reopened its borders in February, with the caseload drastically reduced.

Liberia, Ivory Coast and the United Nations refugee agency, the UNHCR, agreed in March to resume the voluntary repatriation of the remaining refugees.

The UNHCR says it wants to repatriate 15,000 refugees by the end of the year, starting as soon as Ivory Coast gives the go-ahead.

‘Impatient to go’

Around 50 kilometres (30 miles) from the provincial capital Zwedru, the PTP camp was the sixth refugee centre opened by Liberia, designed for 27,000 Ivorians but now housing around 15,000.

Since 2011 it has offered shelter and a semblance of community on the site of the old Prime Timber Production company for refugees who had been scattered across 300 remote locations along the border.

The hard-baked earth floor melts into a confluence of muddy streams when rain lashes the township during the wet season, while in autumn the heat makes sleeping difficult in the tarpaulin-roofed bamboo and clay huts.

Life is basic but its inhabitants are thankful for a regular food supply, medical care, education, water and sanitation, as well as privacy and shelter.

Deniohon and his family, among 9,000 refugees signed up to be repatriated in the coming weeks, have suffered many privations during their exile in Liberia.

The 47-year-old says his first child dropped out of education because there were no secondary schools available for refugees when the family fled.

“I don’t want his brother and sister to follow suit so I am impatient to go,” he said.

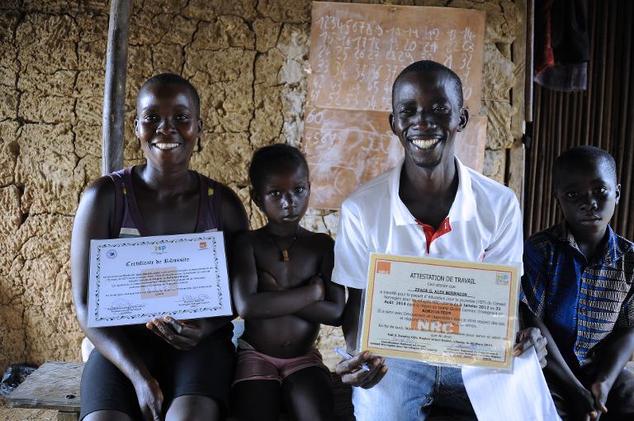

Zeade Gnolo Alex Bernadin escaped the border town of Toulepleu with his wife, two children and nephew as the violence escalated in 2011, walking for days through the thick forest into Liberia.

He says he is keen to return home but fearful of encountering stigma “because our friends may say we are coming from Ebola country”.

No Ebola

In reality Grand Gedeh county was barely touched by the epidemic — there were 11 cases, only three ever confirmed in a lab — and none was registered inside the camp.

Pouho Teide Beatrice, 42, is among many women at PTP who lost their husbands, with pro-Gbagbo militias and forces loyal to Ouattara both accused of summary executions and other atrocities.

“He sent me and his daughter ahead and he decided to remain. When I reached the refugee camp here I received the news that he had been killed.”

“It is time to go now because there is peace in Ivory Coast. I have to take back my children so that they can go to school.”

Both countries plan to tighten security during the repatriations, while roads, little more than uneven dirt tracks in the border areas, will be repaired to allow convoy movements.

The UNHCR says the returnees will be screened for Ebola on both sides of the border and provided with food, cash, cooking utensils, blankets and other items.

They will be taken from a transit centre in Ivory Coast to their villages of origin or choice to rebuild their lives.

“If the vehicle was packed right now I would leave everything I am doing and get on board,” Beatrice said.

“Life in Ivory Coast is far from the one we are living here. I am tired living here.”